Immigration officials are moving to deport at least 150 Bosnians living in the United States who they believe took part in war crimes and “ethnic cleansing” during the conflict that raged in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

In all, officials have identified about 300 immigrants who they think concealed their involvement in wartime atrocities when they came to the United States as part of a wave of Bosnian war refugees fleeing the violence. With more records from Bosnia becoming available, the officials said the number of suspects could eventually top 600.

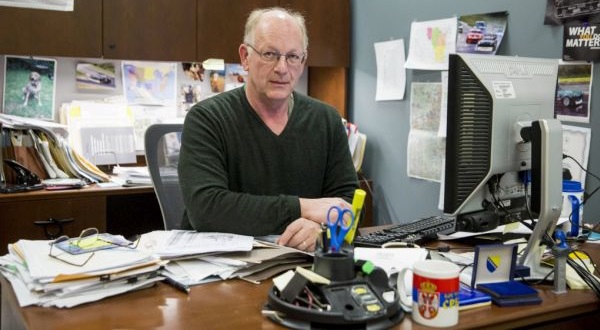

“The more we dig, the more documents we find,” said Michael MacQueen, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement historian who has led many investigations in the agency’s war-crimes section. The immigrants, many of them former Bosnian soldiers, include a soccer coach in Virginia, a metal worker in Ohio and four hotel casino workers in Las Vegas.

The effort to identify suspects included an appeal broadcast to Bosnians around the world in February, urging witnesses to come forward with any information they might have about war crimes. Bosnians should be confident that “justice can be served in the United States despite the fact that many years have gone by and that the conduct occurred overseas, far away,” Kathleen O’Connor, a human-rights prosecutor at the Justice Department, said in a message translated into Bosnian on the government-financed Voice of America network.

Evidence developed by immigration officials indicates that perhaps up to half of the 300 Bosnian suspects in the United States may have played a part in Europe’s worst massacre since World War II: the 1995 genocide at Srebrenica, where Bosnian Serb forces executed some 8,000 unarmed Muslim boys and men.

“The idea that the people who did all this damage in Bosnia should have a free pass and a new shot at life is just obscene to me,” said MacQueen, who investigated Nazi suspects in the United States before turning his focus to the Bosnian war.

The investigations have proved complicated, sometimes dogged by years of delays and legal battles. Funding for the war-crimes center at the immigration agency has been cut, officials said, and with just $65,000 last fiscal year for expenses such as travel and translating, MacQueen routinely borrows a friend’s apartment when he travels to the Balkans to interview witnesses, he said. Officials say they do not have enough money to chase down all of their leads. “The money absolutely makes a difference,” said Mark Furtado, a senior official at the agency.

Lawyers for some suspects fighting war-crimes charges say federal officials have gone too far in linking longtime residents of the United States, some of them now U.S. citizens, to crimes committed two decades ago in a foreign war zone.

“It’s guilt by association,” said Thomas Hoidal, a lawyer in Phoenix who represented two of a group of 12 Bosnian Serbs in Arizona now facing deportation over charges of war crimes.

Since the immigration agency opened its war-crimes section in 2008, it has investigated immigrants linked to abuses in conflicts in El Salvador, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Rwanda and other global hot spots. But no conflict has generated as much attention from investigators as the Bosnian war, which killed more than 100,000 people and displaced 2 million from 1992 to 1995 after the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Amid widespread lawlessness, all factions that fought in Bosnia — Serbs, Croats and Muslims — carried out brutal, ethnic-fueled attacks on civilians. But the Bosnian Serb forces, under Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic, were implicated in far more bloodletting than any other group as they sought a Serb-dominated Bosnian state.

In 2004, the United Nations declared the slaughter at Srebrenica, near an enclave protected by the United Nations, an official act of genocide. The International Criminal Court at The Hague has convicted nearly 80 people for Bosnian war crimes, with verdicts upheld in January against five Bosnian Serb military officials.

But many offenders were able to get away.

When more than 120,000 Bosnian refugees began applying for U.S. visas in the mid-1990s, they were required to disclose military service or other allegiances that might have suggested involvement in war crimes. But the system relied largely on the honesty of the applicants, and there was little effort to verify their statements.

The effort to identify Bosnian war-crimes suspects began with an arrest in Boston more than a decade ago. A series of tips, along with a book by a Boston Globe reporter, led federal agents in Massachusetts in 2004 to a construction worker named Marko Boskic, a Bosnian Serb accused of carrying out executions at Srebrenica. He was convicted of concealing his army service, sent back to Bosnia and sentenced to 10 years in prison for crimes against humanity.

Immigration officials said the case showed former soldiers and others implicated in Bosnian war crimes had been living openly. “All of these people really came into the United States under the radar,” said Lara Nettelfield, a scholar at Royal Holloway, University of London, who has written extensively on Bosnian war crimes. “There really wasn’t much attention given to this problem for years.”

Relying on a trove of Bosnian war-crimes files and military rosters, federal officials have built cases against Bosnian immigrants from New York to Oregon.

In a case in eastern Ohio, a federal grand jury in December indicted an Akron foundry worker, Slobodan Mutic, a Bosnian Serb, on what appeared to be a run-of-the-mill charge of being in the United States on fraudulent immigration papers. The indictment did not mention that he was the subject of a lengthy war-crimes investigation.

While most cases involve Bosnian Serbs, officials have also taken action against Bosnian Muslims and Croats they believe participated in attacks against Serbs, a reflection, officials say, of their willingness to pursue Bosnian offenders of all types.

Trafika|Ba|www.seattletimes.com